"The Vibrant Restraint of Jackie Brown" by Ron Evangelista

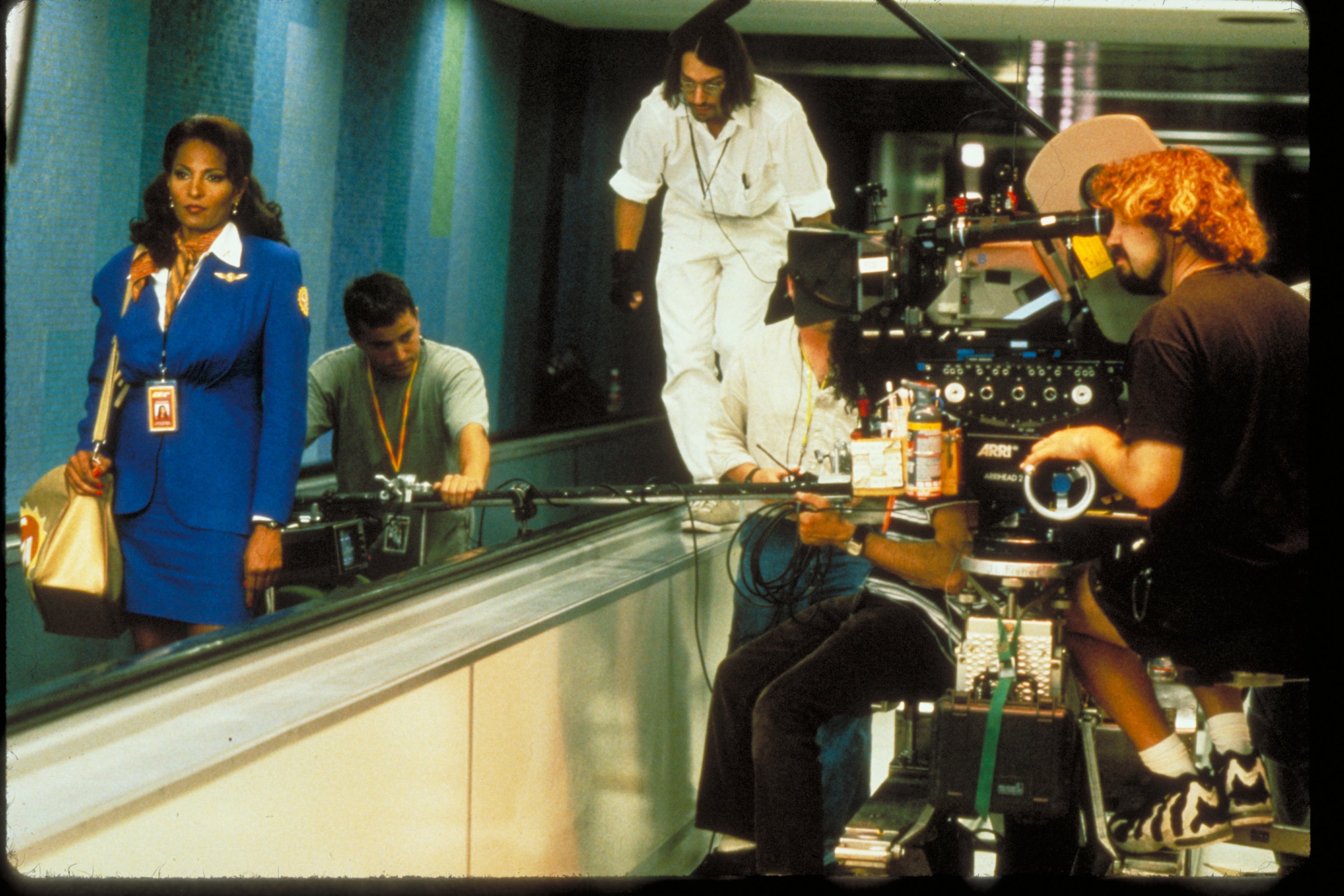

After the thunderous success of his first two directorial efforts, Quentin Tarantino went against the grain and released Jackie Brown, an adaptation of the Elmore Leonard novel Rum Punch, which in its own way, showed viewers a completely different side to the filmmaker — the signature gruesome, blood-soaked spectacles replaced with a grounded and fundamental approach to storytelling. In hindsight, this was probably the best way to present the inherent vitality of this tale. The titular character, Jackie Brown (Pam Grier), is on the run from a lot of things in her messed-up life, including a standing association with Ordell Robbie (Samuel L. Jackson), a drug and gun dealer who makes no qualms about perpetually silencing snitches and turncoats.

Rather than go a similar route, Tarantino simply lets the vibrant characters he created take center stage, allowing their participation in the intricate unfolding of events to be the effective replacement for the Mexican standoffs and brutal deaths audiences expected. It is, as the filmmaker himself famously coined, a “hangout” movie, a film that essentially makes viewers spend intimate moments with the characters — and Jackie Brown does exactly that. The people in this tale are infused with the trademark brushstrokes that Tarantino himself institutionalized in the annals of film history — the sardonic, pop-culture-infused exchanges and diatribes of intriguing personalities involved in absurd circumstances are on full display. Beaumont, Ordell’s former associate (hilariously portrayed by Chris Tucker), gets lured to his death by a mere mention of some chicken and waffles, right when he was presumably experiencing the munchies. Louis, Ordell’s henchman (an under-the-radar performance from Robert De Niro), managed to sign his own death warrant after he failed to control his temper and shot his accomplice, Melanie, in broad daylight (Bridget Fonda). Even Ordell himself was entangled in this farcical web, dying in a way that a criminal so meticulous as him could have seen coming from a mile away.

This prudence works its magic in perhaps its most essential facet: the growing endearment between Jackie and Max Cherry, an aging bail bondsman who is presumably at the tail end of his profession. In a career-reviving performance, Robert Forster brings a pleasant gravitas that bounces perfectly well off of Grier’s sentimentality, hidden beneath a tough-nosed exterior. There is nothing more to be done except to soak in the terrific chemistry of two seasoned actors — a rudimentary smile here, a short listening session to The Delfonics there, and the screen brims with unbridled passion, longing, and affection. By the film’s end, where the two lock lips for the first and final time, it feels like two smitten teenagers reincarnated into middle-aged star-crossed lovers.

Often, discussions circle around its form. It’s almost always viewed as a tribute to blaxploitation films, with the casting of blaxploitation icon Grier in the main role, as well as textual allusions to her past works, hammering home that point. However, to brand it as solely a “blaxploitation” film is a disservice (almost an insult, really) to what it truly is. At its very core, Jackie Brown is a Tarantino-esque love story — a tasteful, realistic, and utterly devastating tale of two people from two very different worlds finding solace in each other, and ultimately accepting that their paths are too far off to ever converge.