The Demonic and the Divine Paul Verhoeven’s BASIC INSTINCT By Robert Meyer Burnett

Basic Instinct (1992) sears with ambiguity, a thriller that dismantles its audience’s comfort with every deliberate frame, forcing us to grapple with the uneasy union of sex and violence. Under the ferocious direction of Paul Verhoeven (for his fourth English language film, behind Flesh and Blood [1985], Robocop [1987], and Total Recall [1990]), whose work has always blurred the line between critique and celebration, this film refuses to play by conventional genre rules. Less a murder mystery than a simmering duel of wits, attraction, and power, the film remains a dance between two characters: one deadly, one determined to uncover the truth, but perhaps not the whole truth. Verhoeven, a maestro of provocation, channels his talent into a film that doesn’t merely entertain, but tantalizes, unsettles, and forces its audience into a confrontation with the darker corners of human nature.

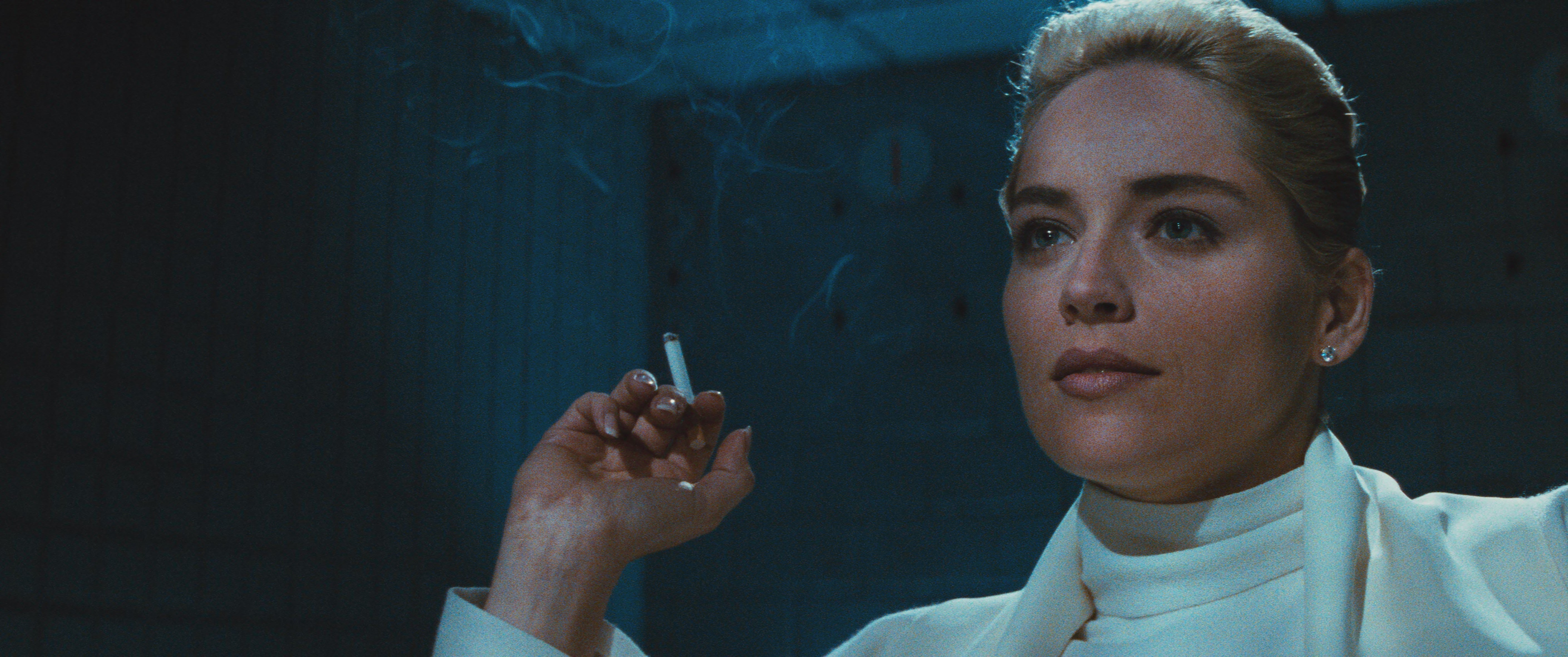

From the outset, the film oozes with the inescapable fatalism of noir. San Francisco, glistening in sunlight, and yet also drenched with neon, fog, and rain, provides the backdrop for a world where beauty and menace coexist. Shadows devour every corner of the frame, and the glitter of opulence only underscores the moral decay lying beneath. It is a slick, seductive veneer, one that perfectly encapsulates Catherine Trammel, portrayed with chilling precision by Sharon Stone. Trammel is a woman of sharp contradictions: a successful writer, a potential murderer, a siren whose beauty could just as easily be her weapon as her allure. Is she the femme fatale or simply a woman toying with the male gaze and its inherent power imbalances? Verhoeven’s brilliance is in refusing to answer this question, maintaining a shroud of ambiguity that ensures no one, not even Trammel herself, is ever fully revealed.

Stone’s performance is a revelation. Her Catherine is self-assured, calculating, and utterly in control. She doesn’t just play with the men around her; she cuts at them, exposes their weaknesses with the precision of a surgeon, and leaves them to flounder in the aftermath. The question of her guilt or innocence, so tantalizing to the audience and the characters alike, becomes secondary to the fact that Catherine understands exactly how to manipulate those around her. She’s not a victim, but a master of the psychological game she plays. She wields her power like a scalpel, not to wound, but to slice away at the fragile facade of control that society demands of its women.

Verhoeven’s themes of manipulation and power extend beyond Basic Instinct into his earlier film The Fourth Man (1983), which similarly delves into the sexual politics between men and women. Both films are sumptuously shot by longtime Verhoeven collaborator Jan de Bont, who exquisitely captures both the beauty and the power of their antagonists. Both films present women who are fully aware of their power over men. But where The Fourth Man offers a more tragic femme fatale, Verhoeven’s Catherine is wholly unapologetic in her manipulation. She commands every situation, every character who crosses her path, while the men around her are fumbling, lost in their own desires and insecurities.

The screenplay, by Joe Eszterhas, crackles with provocative tension. Written in the 1980s and famously selling for $3 million at the height of Hollywood’s speculative-script bonanza, the seductive pages are filled with double meanings, playing on audience expectations, then subverting them with each twist. The dialogue teases us, promises to satisfy our need for answers, only to leave us dangling in a state of perpetual uncertainty. Eszterhas revels in withholding, in playing a game with the audience as dangerous as the one between its leads.

But it is the unexpected chemistry between Sharon Stone and Michael Douglas that elevates Basic Instinct into the realm of true psychological warfare. Douglas, initially hesitant about Stone’s casting, finds himself matched in intensity by the actress, who, at the time, was not yet a major star. Their scenes together are scorching, a clash of egos and desires. Almost as morally ambiguous as Catherine, Douglas‘s performance as the burnt-out, drug-addled Nick Curran, who may have shot an innocent civilian while under the influence, manages to somehow also come off as vulnerable and very human while carrying the audience along on his quest for the truth. In any other actor’s hands, Curran might have come off as repugnantly irredeemable, but Douglas somehow makes the character sympathetic. Like his partner, Detective Gus Moran (played by the always endearing George Dzundza), comments, the audience understands that Catherine Trammell, who Verhoeven himself described as Satan, is in possession of (as the script so eloquently remarks) that “Magna cum laude pussy that done fried up your brain,” which no man…or woman…could possibly resist.

Along with Jan de Bont, Verhoeven’s continued collaboration with composer Jerry Goldsmith and editor Frank J. Urioste (who, along with Stone, were all veterans of Total Recall) brings Basic Instinct to a boil, never allowing the audience to catch their breath. Goldsmith’s score, arguably one of his best, pulses with a haunting, predatory rhythm, while Urioste’s precise editing amplifies the tension, ensuring that we are never allowed to settle into comfort. Each cut feels like a step further into the maze that the characters, along with the audience, remain trapped within.

Basic Instinct does not shy away from controversy, particularly in its portrayal of bisexuality through Catherine Trammel. Critics, especially LGBTQ activists, have decried the film for reinforcing harmful stereotypes, linking bisexuality with violence and manipulation. But the film doesn’t seek resolution, it seeks to provoke, to make us ask uncomfortable questions about sexuality, violence, and power. It challenges us to confront these issues head-on, refusing to provide easy answers or safety nets. It’s this complexity, this refusal to settle into neat boxes, that makes Basic Instinct so unforgettable.

In the end, Basic Instinct is a film that lingers. It doesn’t give us answers. It keeps us uncomfortable, off-kilter, always questioning, always searching for meaning that may never fully be revealed. And that, in its own way, is its greatest triumph — because a film that keeps you wondering long after its conclusion is a film that will never be forgotten.